When we think about the city, most often, we want to diagnose. We think of the city as dark and insurgent, as dysfunctional, as the pan for capitalist consumption. The city becomes a foreboding monster – a ruin of ideals, where people, sphinx-like, emerge to produce and consume. Perhaps it is the visage of the city as a source of political order and social chaos, and a home of diversity and boundless promise, that attracts creatives and non-creatives. And creatives have made it their business to image it in various forms and angles.

Poets have talked about cities since the beginning of time. In the Bible, Jeremiah laments of the destruction of Jerusalem, a funeral dirge for the loss of a city, rent out in acrostic verse. We recall Tyrtaeus, the first poet of Greek city state, who composed verses in Sparta. Possibly no other poet in post-colonial Africa has mapped a city – in so few yet so powerful words – as J.P. Clark in Ibadan.

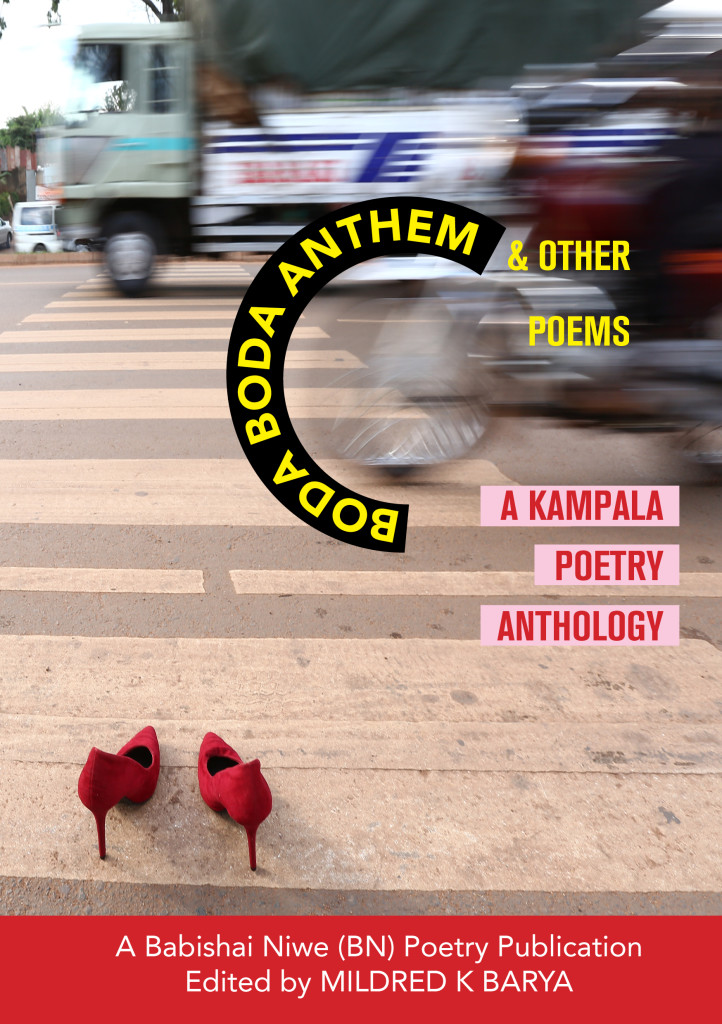

Babishai Niwe (BN) Poetry Foundation, under the guidance of Beverley Nambozo Nsengiyunva, set out to imagine Kampala through poetry, leading to the publication of Boda Boda Anthem & Other Poems edited by Mildred K Barya. The idea of a Kampala Poetry Anthology is not only ambitious but a first in Africa. This is the second anthology by the Foundation which also presents the annual BN Poetry Award. The first was A Thousand Voices Rising.

The poems in Boda Boda Anthem & Other Poems are loosely grouped into four thematic areas: ‘Ubuntu’, ‘Kampala City Y’ani’, ‘How Do You Say Kampala with an Accent’, and ‘Marry Me, Kampala’. These are portraits of Kampala, but they not wholesome portraits enclosed in burglar-proof glass in national museums. They are fragmented and produce a shock of the real, not unqualified imaginaries, but testimonial literature – a documenting of an age.

The poem, Boda Boda Anthem, introduces us to the chaos of Kampala. Boda bodas are imaged as ‘hordes of demons searching/Packs of hounds game hunting/death throttles clamouring for blood’. These boda bodas whizz through Kampala’s dust-ridden streets leaving carnage and death in its wake. They pride themselves as the ‘unbwogable force of renegade commandos’. ‘Unbwogable’ is a peculiar word here, Kenyanism, coined from a Luo word ‘bwogo’ meaning to ‘scare’. Unbwogable means ‘you can’t scare me’. The term originated from a song by Kenyan rap duo Gidigidi Majimaji. Though not initially meant as a political theme song, it was picked up by strait-laced opposition politicians and became an important cultural force in dethroning President Moi after 24 years of dictatorship. The use of such a term to describe the throttlehold boda bodas have on Kampala streets presents a grim picture of ‘ghost riders on wheels of steel’ conquering and terrorising a city. One wonders whether boda bodas are the cause or the consequence of a city’s (dys)function. One wonders if boda bodas are a political metaphor. Metaphors, from the Greek word metapherō ‘carry over’ meanings. In Contagious Metaphor, Peter Mitchell says metaphors ‘establish equivalences’, ‘scratch the surface’ and allow readers to establish the link between the abstract and the concrete. Boda Boda Anthem & Other Poems is rich in rhetoric that scratch the surface and leave the reader to traverse the luminal zone between the metaphorical and the material.

In Larok from Napak, Kampala is pictured as a concrete jungle. Katanga captures degeneration accompanying consumerism: ‘a/ State-kept /rubbish heap of /Shit Condoms Cigarette butts Tots and People/. The narratives of daily surviving the city litter almost every page. In Two Mighty Hills we are informed that Kampala is ‘a city that is no longer safe for a frog’, yet despite the tone of desperation, the poet still ‘longs for a day when he will/Call Kampala a home of patriots/ Not genuflecting purists.’ Froth, laments the brutality of law enforcers, while Bring then Take laments economic dispossession by the Chinese: they ‘bring in all they can to sell/ they bring in the machines plus the construction materials for the roads./ The Chinese take away all they can’. In U@50 a poet asks Kampala: ‘will you slip into menopausal madness?/ Become a beneficiary of memory lapses,/ Reminiscing about the bush ol’ days?’

Kampala does not kill all her cubs. In Unveiling My Bride Kampala, we find an effusive tone – coy and seductive: ‘My beautiful bride Kampala/ You make my heart sing lalala/ My heart cannot stop staring at you… / On you I will spend all my money/ If that would impress you, honey.’ In Rolled Eggs we are told that “you have not known the true taste of Kampala until you hold in your hand/ Something more precious that your silver watch, (two chapattis and rolled eggs) a Wandegeya Rolex’.

We cannot blame the poets for giving us only passing glimpses of the whole. There is no single image of a city. Kampala is a concrete jungle to some, the Canaan of matooke and pork to others. There are Two Sides of Kampala: one is comforting and gives the confidence of an organised, disciplined, and clean ambience, the other embraces the night’s evil veil and sends cold shivers down people’s spine.

Cities are dynamic, perplexing, and uncertain; notoriously difficult to map, and in most cases, the territorial boundaries of cities no longer exist. They have morphed into fictions that expand with every leap of imagination. One asks: are the poets talking about Kampala or Uganda? Are they talking about Nairobi, Lagos, or Johannesburg? As a reader, one is imprisoned in endless comparisons. Does Kampala have chaotic energy? Does it share the clockwork rhythm of daily life with other metropolis? What are its streets, its people, its dreams like? The imaginable-ness of Kampala is further compounded by the fact that the anthology features poems from eighteen countries. It is a diverse mix of voices whose images of Kampala cannot be pigeon-holed into a single interpretive lens.

The quality of the poems is diverse. Some voices are becoming, some are young – the breadth of introspection no more than the dainty sprint of a young impala on Kampala’s undulating hills – but others are mature and intense. The anthology has weak and strong threads. We are free to judge how well different poets see, or unsee, Kampala.

One thing is certain though, like A Thousand Voices Rising, this anthology – Boda Boda Anthem & Other Poems – is definitive of the rising stature of Kampala as a literature convent and a drinking hole for African poets.

Boda Boda Anthem & Other Poems will be launched on Thursday August 27 at Goethe –Zentrum Kampala, Bukoto Street. The book is currently available in bookshops and can be ordered directly from BN Poetry Foundation.

Richard Oduor Oduku (@RichieMaccs) is a poet and writer. He studied Biomedical Science and Technology at Egerton University. He works, as a Research Consultant and lives in Nairobi. His work has been published in Jalada Africa, Saraba Magazine, Storymoja, San Antonio Review, among others. He also writes for #MaskaniConversations in the Star Newspaper. He is also working on a novel and a collection of poems and is a member of Jalada Africa (a pan-African writer’s collective) and Hisia Zangu (a writer’s and art society).

Find the programme for the Babishai 2015 Festival here: http://www.bnpoetryaward.co.ug/babishai2015festival-is-here-launched/

[…] When we think about the city, most often, we want to diagnose. We think of the city as dark and insurgent, as dysfunctional, as the pan for capitalist consumption. The city becomes a foreboding monster – a ruin of ideals, where people, sphinx-like, emerge to produce and consume. Perhaps it is the visage of the… […]

You’ve convinced me. Will try to grab a copy next time I’m in town.