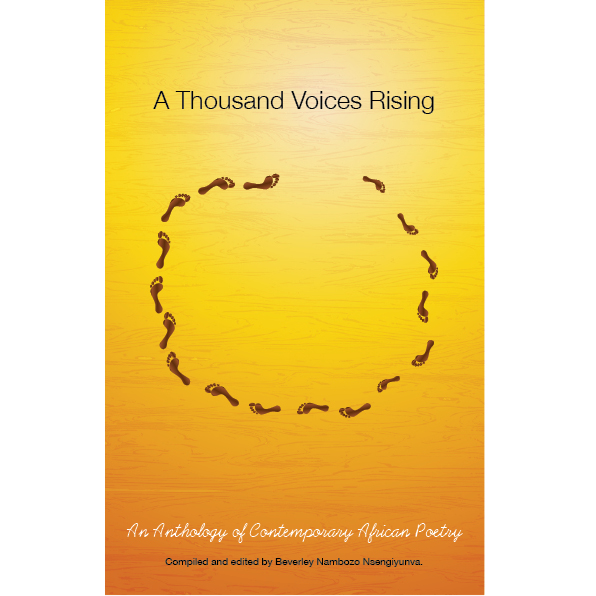

When you open the first page of the poetry collection A Thousand Voices Rising, Beverley Nambozo, begins with what appears to be a sales pitch. “This is an exquisite tapestry of words”, she says in her elaborate Foreword.

The ‘sales pitch’ dissolves into a solid statement of truth as you meet the words of Orogot Pamela in her poem A Face Like Mine. Orogot paints a collage of life’s pain and struggles. She speaks of a baby abandoned on the hospital bed. The baby is unknown, perhaps one of the African kids rescued by the Redcross from the battle fields of DRC Congo or Jonglei State, South Sudan.

It’s a collection that speak of human suffering – or African suffering in the case of war and hunger – but the collection covers hope and the beautiful butterflies of our African autumn. And true to the book, hope is not just looking forward to the death of all African dictators or the sudden emergence of milk wells and rivers of honey.

Barbara Oketta in her beautiful poetical mint, Better at Dawn, points to the little hopes we can enjoy. I say Better At Dawn is figurative in many ways. Beverley Nambozo has waited for her dawn to compile this great collection as there are many problems in the publishing industry. Oketta, not directly and purely on my own interpretation as a writer, calls them the clatter of cups and saucers and the barking of the neighbour’s dogs.

We love our countries just like Kalanzi Kajubi glorifies his country, Uganda. He was born in the pearl of Africa. I love Kenya and I have been in Uganda – those folks cherish their country but every country has her a flip-side, which is mostly a stinking closet:

“…Now my pearl seems to lose its glimmer as it’s muddied by deceit, poverty and violence. She grows weary as her mountains turns into cages.”

The flip sides are perhaps the pots that are boiling in James Dwalu’s The Careless Cook. It’s a short poem that speaks volumes about how badly we sometimes do things in our own countries. Our pots are boiling with corruption, extrajudicial killings, bad roads, and poor services. This is because we are bad cooks – bad leaders.

Africa is a continent blistered and festered with scam leaders. Just like Apuuli Mugasa’, in No Change, we know them. They’re men with large notes; the unashamed folk who walks past the beggar (perhaps the citizen) in the streets and dips his hands into his pockets but he has only a ten thousand note. He walks away. Later, he reminisces over what he saw; “I looked at the window in his ragged shirt and saw where cold had licked his skin; his eyes opened a hole in his heart where love and warmth never pitched tent.”

Emotive events that scarred the continent are also immortalised. Everybody remembers the deplorable events that started on the April night of 1994 in Rwanda and commandeered the global headlines for 100 days. Michaella Rugwizangoga reminds us of the cries of the victims: “…I was not the only one crying for the blood spilled, for in the sky of April 1994 even the stars were mourning…” The victims knocked at the sun’s door and the moon’s door but nothing happened. It is not only Rwanda where people have been ‘wearing this black veil’ and obviously ‘not the only one crying for the blood spilled’.

Richard Ali cries over Darfur: “We do not dance any longer in Darfur, no swaying veils.” No Dancing in the Sudan is another provocative piece that salts our wounds and pierces our collective conscience. Jason Ntaro, in One day, someday will be this day, asks; “But who is to blame? Us or those who choose to rule us? The rebels or those that feed the rebels’ gun lust?”

Harriet Anena is a stinging poet. Oyet Sisto, in review of her beautiful collection, A Nation in Labour, says that she has “a mastery in politics, war, love, and healing.” That mastery is forceful in the subtle sarcasm in We move on.

Every collection must see through trouble and tell the readers that come tomorrow, the shackles and fetters shall loosen their stranglehold. The more you read this collection, the more writivism becomes real. Many Mandela’s, Steve Biko’s, Achieng’ Oneko’s, and many other activists have been reincarnated. Even though they don’t pull crowds at the Kamkunji grounds, they will surely pull a crowd of readers.

May be there are weaknesses of some individual poems but the agenda is well discussed in A Thousand Voices Rising. But like Lagos, Bode Asiyanbi’s poem, this collection is about “water, dust, laughter, and sweat. It’s about “generators whining like mutant bees, sprawling off off the womb of Yemoja”.

This collection is “relentless grip of passion, like mating crabs on the seashore”.

Oduor Jagero is a Kenyan journalist, documentary script writer, poet and novelist with his novel, True Citizen. Read his interview on Sooo Many Stories: Lessons on self-publishing from Oduor Jagero

///

You can buy a copy of A Thousand Voices Rising here: http://www.bnpoetryaward.co.ug/product/anthology-african-poetry/

Thanks Nyana and Jagero, beginning with a sales pitch-that’s what I do. wow! You’re right when you say it’s a relentless grip of passion.

Thanks so much.

Dear Nyana,am a Poet from Gulu ,Northern Uganda my poetry boo”But My heart” is being Published by Nissi Publishers,Ntinda.Kampala.I here by had wanted to inquire if you can do just the review.

Thanks

Send me an email and let’s talk about how you can get it to me. email address: kaboozi@somanystories.ug