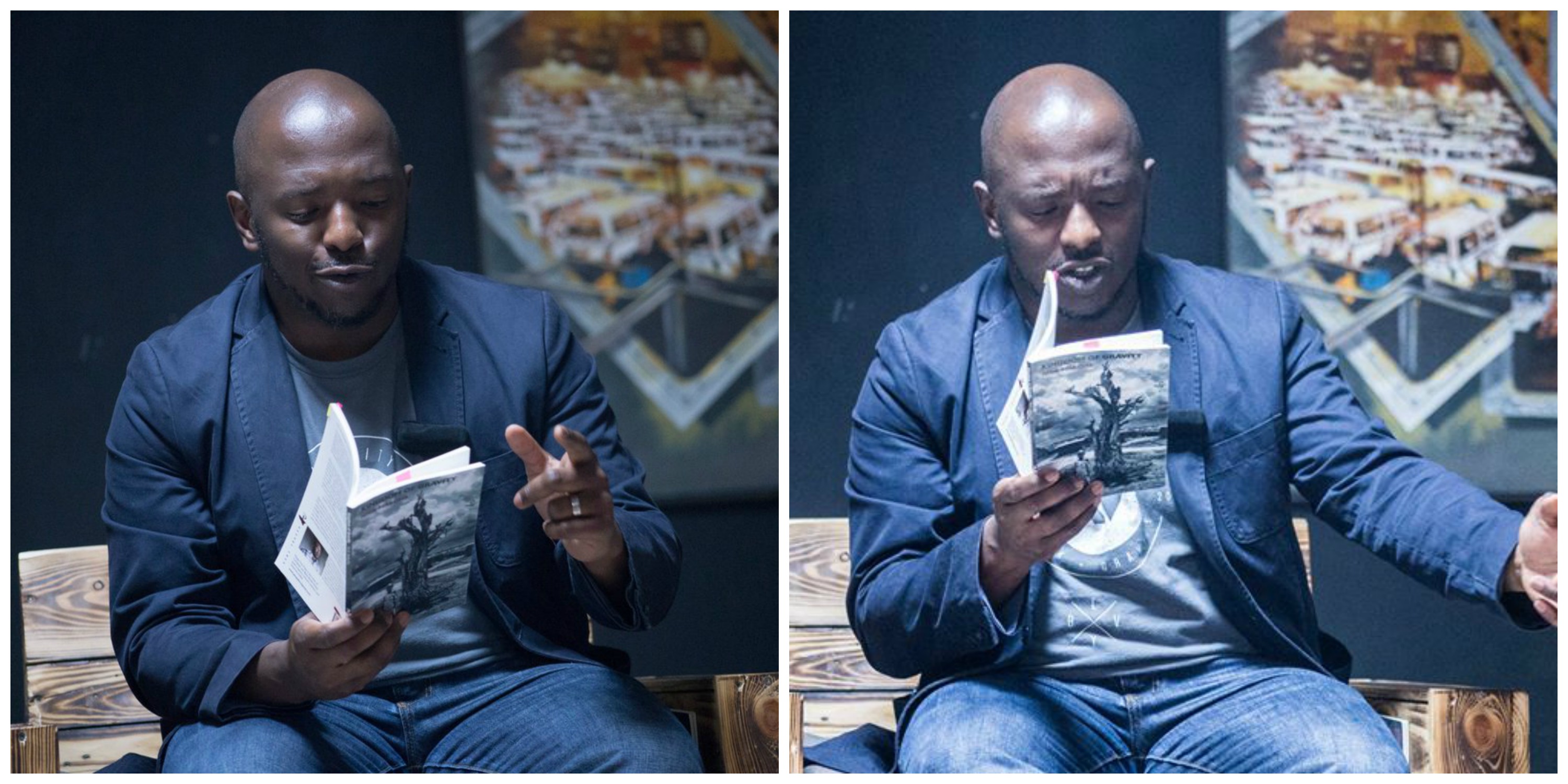

Nicholas Makoha is a dynamic writer and poet of Ugandan origin, raised and currently residing in London, UK. He is the 2016 winner of the Toi Derricotte & Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize for his manuscript Resurrection Man, soon to be published. He won the 2015 Brunel International African Poetry Prize and is on the 2017 shortlist for the same prize. Nick was in Uganda recently to launch his first poetry collection, Kingdom of Gravity and oversee a workshop of budding Ugandan writers organised by Writivism. Over drinks, we had a chance to chat.

When was the last time you were back in Kampala?

I was here for my sister’s wedding in 2015. So being back here has been really good; I got to spend sometime with my dad and his family and spend some time with my sister. Yeah, my sister has pretty much hijacked me every night. (laughs)

You’ve interacted with a few creatives here in Uganda. Give me three words you would use to describe the creative climate in Uganda right now.

What’s clear is a passion for creating initiatives for writers. I definitely want to be a part of that. I am not an expert myself, but wherever I can contribute to my own people and towards African literature, I’m interested in that conversation.

What I would say is it’s also relatively new, a new phase of the literature experience. There is a possibility that groundbreaking work can be done with the writers of this generation.

My third word would be open. The writers are open; at least the ones I’ve been working with. They are open to the ideas and challenges I’ve put before them. I’m quite a hard taskmaster, and they’ve been positively responsive to that.

At what point in your education or your life did you realise that the creative path was yours?

There are different parts to this answer. If I’m looking back now, I can say I was always a creative but being from a Ugandan and African background, our parents taught us to be scientific. They wanted us to be accountants lawyers, you know. So I was following that path because I was good at those things but I think when I was at university, the creative spark started to show. On the weekends a friend of mine was attending a drama school and he invited some of us to go along and we started to do drama, started to sing. I was there for two years because you could only stay till a certain age. And on our graduation day which was a showcase, I shared some poetry, instead of singing or acting. It wasn’t that good in hindsight but it was the beginning of me exposing myself to the outside world as a poet because internally I always considered myself one. That’s when it started for me. As I left university, I started to perform in spoken word clubs all over the city. Then at some point I wanted to make it a career. So I remember sitting at my desk in the bank and thinking you know what? I can’t see my life being this. I wanted to do something that would inspire my to-be wife and children. And what was I passionate about? Poetry. I didn’t know how I was gonna make it work but I knew I had to.

What was your family’s reaction? Did you feel pressure to stay within the conventional working system?

I don’t think that pressure is just from family, I think its societal. One of the things we were discussing in the Kampala workshop is the world’s view of the writer. Writers are considered romantics, day dreamers, lazy and drunks. So a lot of the time I had to hear these jives either from my family members or friends or people I’d meet. You have to find a way to be gracious about it and not let it hurt you. It’s upsetting but if you let that win then you will stop trying to make it. And there are no set paths especially for a writer of colour, you know. I didn’t go to Oxford or Cambridge. I didn’t study English at university level. It wasn’t set for me to be a writer, so I have literally carved my own career.

So let’s talk about that a bit. You being a man of colour. How does it influence your work? Has it been a struggle establishing yourself in the creative industry in a country where racism is quite prevalent.

It is a struggle because people see my colour before they see me and they have their prejudices towards me even before they’ve heard a word out of my mouth. So a lot of time I’m having to navigate through people’s prejudice before they can actually take me seriously or navigate through my own prejudices so that I can take myself seriously. I was listening to a talk the other day and someone asked, “Does a white man ever have to think about the colour of his skin before doing anything?’” Well, I have to. A situation in which I raise my voice will make me look excessively aggressive and I’m just raising my voice or I could be in a neighbourhood and I automatically become the attacker. Does that mean I am not allowed to be scared in that situation? See you are robbing me of parts of my humanity, merely because you have a perception of who I am because of the colour of my skin. This is something I have to negotiate daily, no day off. And not that I allow it to affect me, it’s just a constant reality.

In society generally, opportunities that might be available to many other groups are not necessarily always available to people of colour.

Would you consider yourself a successful artist monetary wise?

Hmmm…not yet. Not monetarily. When I land the big house and nice car, no worries about bills then I can say I have arrived. But I think I am reaching my peak in artistic terms. Winning awards, being able to go on certain courses, having my book published. I think I am a better writer today than the young man that performed at his graduation. I am however, still a work in progress.

Any advice for the creatives that might be struggling to leave the creative industry for the uncertain income of the creative path?

Money is always going to be a problem. (Laughs) But I think it begins with perceiving yourself as an international artist. That is, I had to be open to where I could go around the world or even within my own city to develop my writing. So I haven’t got the money but let me start earning through commissions etc, as I improve my craft. Because if I write better the possibility of getting published increases. So you are always trying to increase the possibility for success.

I think you also need to build a community of good writers and mentors around you. Almost like building an infrastructure. I have always been surrounded by mentors and attended workshops that have allowed me to become the writer I am today.

Also, don’t focus too much on whether there is money or not, if you are a writer, you write. Just do it! Not that money will take care of itself, but it’s more about cultivating the craft and discipline of writing.

Let’s talk a bit about the Youth Poetry Network. Describe that for me.

I used to work with an organisation called Apples and Snakes and I had some friends who were writers and they and a lot of people were calling me to work with younger age groups. So the Youth Poetry Network was setup to help young people. What I realised is a lot of young people go through trauma and if you ask a child to sit and write, they are not going to want to write if they can’t even talk to their dad or if mum is suffering cancer. Because as children we are kind of silenced, with not as many avenues as adults to talk about the things we want to. So the Youth Poetry Network just gives them the space to talk freely or write freely. And what that did is they began to see language as a bridge to communicating with the world.

Thinking of bringing it into Africa and Uganda in particular?

Well I’ve had conversations with a few organisations. I want to give back to my community. So as much as I live in England, I am Ugandan, and I want to contribute especially to the next generation of writers, so this is the frontier for me. This is the first official workshop that I have run in Africa, in Uganda, so I’m hoping there will be many more of these scenarios. I don’t really want these one off ventures. I am hoping more for a hub of writers, within Uganda, East Africa and the whole continent, looking to improve their craft just as I am constantly improving mine.

All the best in your future endeavors Nick, as you continue to take on the literary world by storm.

You can read some of Makoha’s poetry here: Death-Fall and LRH