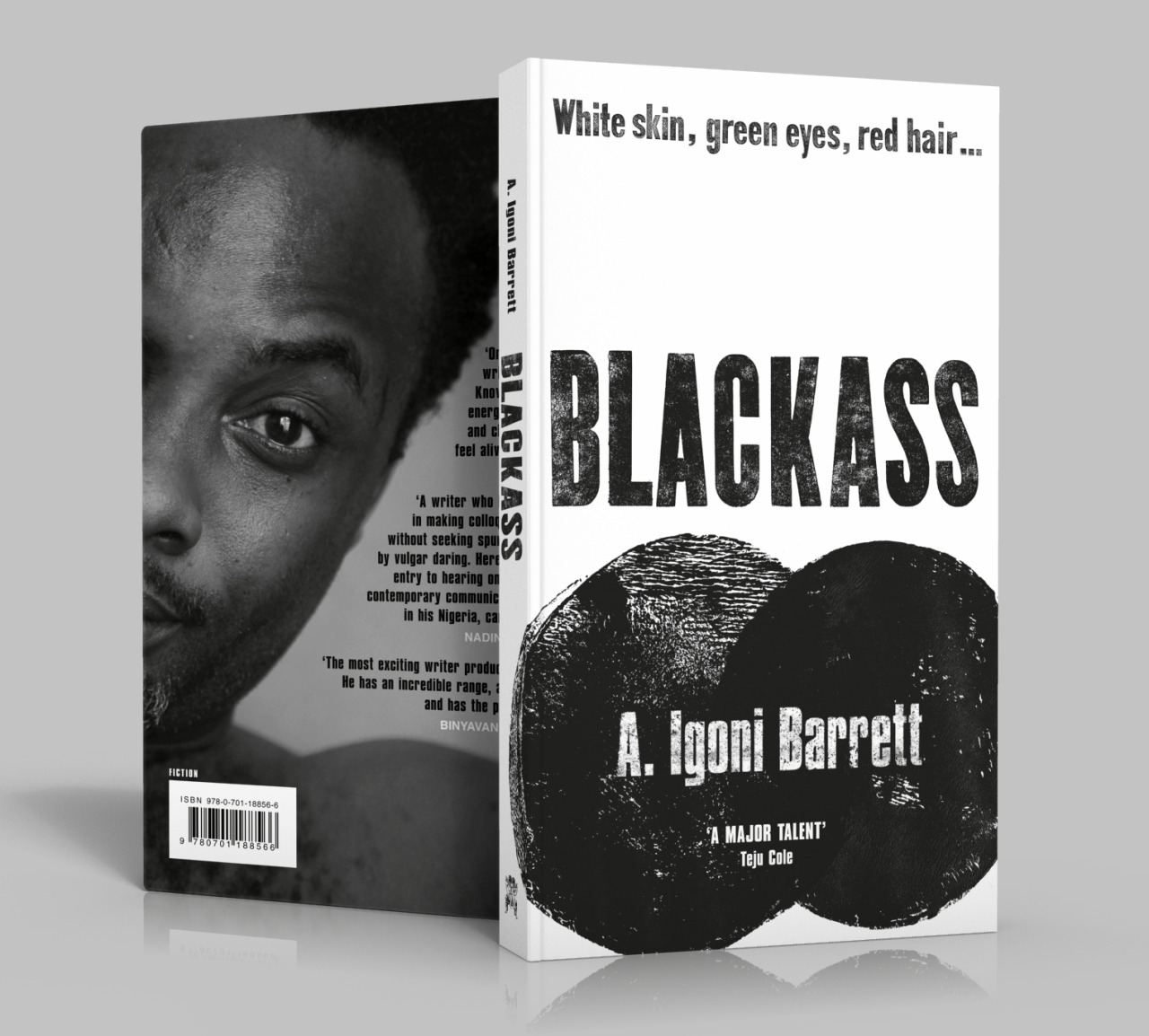

My initial thought about the title Black Ass was free from any racial connotations. A book by an African author had to be about a great African experience that I was yet to read about. And yes, this particular one was different, nothing like what I had been reading.

Igoni Barrett writes about a 33-year-old African man, Furo Warikobo, born in Lagos, who wakes up one morning and he is white, an unlikely transformation with even more unlikely first effects. In a panic, Furo escapes the house without being seen by his family and goes for his job interview. Understandably disoriented and confused by his new transformation, he decides not to return home. He encounters more disorientation on the streets, a white man in a sea of black. But his fortunes turn at a job interview when he’s given attention and respect because he’s white. He gets a senior level marketing job on the spot despite his low credentials. What gives him an edge is familiarity with Nigerian culture; the accent and fluent dialect. Only his name makes his new complexion questionable.

Some of the perks of this new identity include; random women on the street trying to help him get a taxi because the drivers hike their rates at the sight of an “Oyibo” (white person). A beautiful woman in the rich neighborhood of Victoria Island, Syreeta, takes Furo in. She feeds him, sleeps with him, and buys him new clothes all for seemingly nothing, except the privilege of showing him off to her friends married to white men. It is when Furo is living with Syreeta that we learn that his transformation was not as clear-cut as assumed. His ass remains richly black. Later on in the book, we also encounter Igoni, a writer who changes into a woman. Despite her big boobs and curves, Igoni now known as Morpheus, still has a penis. Unfortunately, hers/his was a transformation that wasn’t fully explored by the book.

If you have read Black Ass, you know for certain all that I’ve written so far; therefore I will share my sentiments. First things first, I did not complete reading the book in its entirety however, I was very lucky to discuss it on two occasions. First with the #MEiREAD fireplace by Sooo Many Stories and secondly, in presence of the author A. Igoni Barrett, at this year’s Writivism Literary Festival.

For me to get a book and actually sit down and turn its pages, happens after I’ve read a couple of reviews about it. Black Ass was not an exception to this ritual. I got mixed sentiments from other readers too, one to be exact, that said, “Do yourself a favour and stop in the middle, the last half of the book is horrible.” This gave me more reason to find out what was in the last half of the book. One review called it “a comedy of manners where the author captures his characters’ every foible and amplifies it for effect.”

As a reader, I began to understand how far people, specifically Nigerians, ridiculously go in order to appear important. This can be seen clearly in a section of the book where Furo’s sister uses Twitter as a medium to publicise her search for her missing brother. I also found it interesting that even with the existing statistical information about unemployment, a sudden twist of fate was a clear solution for an unemployed young Nigerian: the mere change of skin. Here in Uganda, I like to believe that if I suddenly woke up as a white woman my fortune would turn in regard to getting a very good job or being treated with utmost respect.

Although the collision of Furo’s new world with old self; where he lived with his parents, happens towards the end of the book, the author intentionally shows us how our choices or decisions as individuals are mutually exclusive from what society or family expects from us. Furo is torn between his desperate need for money and status and his attachment to his family back home.

According to the author, the book is meant to start a discourse about change in society which for me was very literal yet relatable. Literal in the sense that the author had to transform (change) an African character into a white man and relatable in how he shows society’s reactions to this unlikely transformation.

The decisive point is that A. Igoni Barrett opened a can of worms in regard to the several interesting ideas he introduces in Black Ass and I had hoped that they would all be explored.

Annet Twinokwesiga is a regular member of The Fireplace: #MEiREAD, our book club for adults. Want to read about that time we hosted Igoni Barrett? Go here: The Fireplace: #MEiREAD Black Ass (with Igoni Barrett)