When Phirimoni and Noweri got home, they ate Irish potatoes and a groundnuts paste mixed with pumpkin leaves that Maama had prepared before heading out to Nyakabungo market. Kyabihambe forest was on the hill next to their home. The two brothers started their journey to the forest to collect firewood. Phirimoni led the way and Noweri followed at his heel. The younger boy sometimes raced ahead of the older boy but he would pause and wait until Phirimoni was in the lead again.

Abu got to Kyabihambe Forest first. He was delighted to see his mountain of wood still standing high and mighty. Using the panga he had carried with him, he cut branches from the nearby weak trees – the ones he had not cut down because they were too small to make good charcoal. Some branches he reached by jumping high up in the air with the panga raised above his head. To reach more, he had to climb up the weak trees and swing slightly along with the stem, struggling to thrust his arm to a high leafy branch. With each thrust, his black sturdy upper arm contracted into a mould of hard muscle.

When he had collected enough leafy branches, he assembled them near the wood-mountain and left to look for clumps of thick bladed wild grass. There was not much grass in the clearing he had chosen to build his wood-mountain and so he had to walk a distance away to the next fold of the hill.

Phirimoni had carried a small household knife to use for chopping stubborn twigs and branches that he could not break with his hands. As he walked he aimlessly chopped flowers on the pathways and any short shrubbery along the way. Noweri was beginning to get tired and had ceased to run ahead of Phirimoni. The walk to the forest had turned out to be boring. He wished he had stayed at the neighbours’ driving a metallic hoop from the tyre of a bicycle. Topher recently acquired a kipanka. Everyone has driven that kipanka downhill. If I had not come with Phiri, today would have been my chance to drive it, Noweri thought.

The sky was a beautiful clear blue with a few white clouds here and there and the sun shone so brightly that December afternoon. Abu run across Kyabihambe Hill, crossing from one fold to the next, jumping over ridges, arriving at a lash green expanse that had the thickest and heavy grass he needed. With his panga, he dug into the soil, and with his strong hands he uprooted clumps of grass with soil still attached to the roots and he begun to fill the sac he had carried with him.

As Phirimoni walked through Kyabihambe Hill, he picked out the trees with low hanging branches that he could reach. He had to be selective of the trees because all he had with him was a kitchen knife that could not chop into thick branches. It had not been a fruitful harvest so far. They had been walking a while and Phirimoni had only collected a handful of firewood.

He paused in his step as he stared at a heap of branches assembled on the ground, metres ahead of him. This was unbelievable. Of course it belonged to a charcoal burner: he could tell from the high stacked stems standing in front of him and the heap of soil – and – the green branches, but he saw no charcoal burner around. If I am going to do anything, I have to do it now, he thought. Quickly he turned to Noweri who was trudging on from a distance.

“Stay here and look out for anyone coming. I have found firewood,” he said pointing at the branches on the ground.

Phirimoni continued to the branches and started taking off leaves on the ones he thought would make good firewood if put out to dry in the sun for a few days. He worked fast and alert. He knew that most charcoal burners were older people with many responsibilities who often left their stacks of stems unattended to in the afternoons. The actual burning of the wood into charcoal was done in the evening when the sun had set, the heat not being conducive for slow baking of the wood.

Abu was walking back to his wood-mountain, panga dangling in one hand, sac of grass dragging in the other when he noticed a person de-leafing the branches he had gathered earlier. He was immediately displeased with what he saw and he ran down the hill toward his wood-mountain, abandoning the sack of grass because it was heavy.

Phirimoni heard footsteps descending towards him in quick movement. He saw Abu. He knew Abu, the deaf-mute from Kigarama Hill. He went back to de-leafing the branches, not suspecting that the deaf-mute may be the owner of the branches.

Abu reached deep within for the loudest voice he could imagine and said to the skinny brown boy he was seeing at his wood-mountain, “Stop doing that, I need the leaves on those branches, you thief, stop taking my branches.” He attempted to talk but all Phirimoni heard were very comic utterances from Ekiragi.

“Noweri, come and see Ekiragi,” Phirimoni called out to his brother.

Noweri ran to where his brother was to get a good view of Ekiragi. Abu felt a rage rise in him when he read Phirimoni’s lips and recognised the insulting name, Ekiragi. Two veins stood out at his temples and the grip on the panga in his hand tightened. He pointed to the branches and then pointed back to himself, informing Phirimoni that the branches were his. His face wore anger and impatience and intensity almost simultaneously.

“Ma muh uh uhuma ah, keeeee, uh ma,” Phirimoni imitated the sounds Abu made each time he tried to say something.

Noweri laughed even harder and made similar sounds. Phirimoni begun to gather the branches he had de-leafed.

Abu drew closer and asked them to stop. He said that they should stop stealing his branches. He said that the land they were standing on was owned by his father. He said that the wood was his, the soil was his, the branches were his and the leaves on the branches too. He spoke but Phirimoni and Noweri laughed and pointed and laughed and teased the deaf-mute.

Abu leaned forward and with one hand, wrestled the branches out of Phirimoni’s hands, the sharp bladed panga held firm in the other hand. The two boys struggled for a while, Phirimoni claiming ownership of the branches, Abu defending what was rightfully his.

“You daft boy, give me my firewood. It is mine” Phirimoni said to Abu. “Noweri, the mad boy is stealing from your brother,” he called to his little brother. The bundle of wood fell to the ground between the scuffling boys.

Noweri picked a pebble and threw it at the deaf-mute wrestling with his elder brother. Abu said to the little boy, stop throwing stones, and stop it right now. Noweri only laughed and continued throwing pebbles. He knew that people who could not talk or hear were mad and you threw stones at mad people. He threw two pebbles, three pebbles, and then Abu turned to Phrimoni and said to him, “Stop your little brother, tell him to stop throwing stones at me.”

Phirimoni was bent over, binding the sticks of firewood with fibre when Abu pushed him causing him to topple over, face first to the ground. Noweri stopped throwing pebbles.

Abu said to Phirimoni, “This is my father’s forest, why are you disrespecting me in my father’s forest? Who do you think you are taking my branches without asking, throwing stones at me, calling me names, who do you think you are?”

The skinny brown boy got to his feet. The silver blade in the deaf-mute’s hand was angrily flashing at him. Phirimoni picked his kitchen knife from the ground. He begun to run. Noweri ran ahead of him. Then Phirimoni stopped, walked back and threatened to go at the deaf -mute if he came any closer. Although Phirimoni could see that the boy in front of him had a stronger body than his, he was not in the least intimidated because he expected very little from Ekiragi.

Noweri stood still and watched, excited that he was going to see two boys fight. He picked one last stone and threw it at Abu, hitting his forehead. Abu switched his intense gaze towards Noweri, terror in his red teary eyes. Phirimoni laughed when the deaf-mute shouted very unintelligible words to Noweri, nearly biting his tongue in the process.

Abu stepped forward.

Phirimoni said to his brother, “run away and do not get hurt.”

Noweri ran and stood away at a distance where he could still be able to watch the fight.

Abu moved forward.

Phirimoni threw his knife at Abu.

The knife flew at Abu unexpectedly and he did not duck to avoid the hit. It missed Abu’s left eye slightly and bruised his cheek.

Realising that he had actually thrown a knife at someone, realising that he had thrown the knife at someone with a panga, Phirimoni started to run but he tripped when a creeper noosed round his leg. He tried to pull the noose apart. He tried to break through the green tendrils but his grip was not strong enough to set his leg free. He saw the boy standing over him. He saw a silver blade flash like a streak of lightning. He curled on the ground, head shielded between his thighs. Before he could look again, a sharp heavy metal landed on his shoulder. Phirimoni screamed, Noweri heard the scream, saw the blood.

Noweri could not stop the fight. The little boy ran away as fast as he could. He hoped his mother was back from the market. He ran and did not look back. The forest whispered ‘shhhhhh, shhhhh’ as Noweri galloped through the trees, his little legs cutting through the air and squishing scurrying insects on the ground, crushing dried leaves. He ran to get help. He ran to escape.

Phirimoni remained alone, with flagged limps that could not lift him off the ground and a suddenly numb shoulder. Abu did not stop raising his hand; he did not stop bringing down the sharp panga. He continued to cut and bruise and chop. Phirimoni – who remained in the same spot, helpless, unable to scream as loudly as he wanted, at once more aware of how dense the forest was, how far he was from home, how unlikely it was that Noweri would make it home and back with their mother to save him – was surprised at how strong the deaf-mute was.

Abu continued to raise and bring down his panga. He was chopping trees to burn for charcoal, he was cutting down branches to use as a flame regulator, he was cutting and cutting and the liquid gashing out at him was only sap from the trees. He raised his panga one last time, and before he brought it down again, he saw a boy laying in a pool of blood, helpless and limp.

He immediately dropped the blood dripping panga and looked around. He was terrified. What had he done? He looked at the boy laying at his feet and looked around again. He ran away from the blood and the limp body on the ground. Seconds later he ran back. He looked at the boy on the ground again, saw the swollen cuts his panga had left on the boy’s back, shoulder, arms, skull, legs,- what had he done?

He reached out with his hand to awaken the boy on the ground. He knelt beside him and shook him hard but the boy did not budge. The boy’s face was pressed flat against the ground. Abu lifted the face and saw that that the boy’s eyes were closed and his mouth was wide open. He pulled his hands away and the boy’s head fell back to the ground as lifeless as a log.

Abu looked around, he did not see the younger boy who had thrown stones at him. He had blood on his shirt. His shorts had dump patches but being black, it was not obvious that the wet patches were in fact blood. He took off his shirt and threw it at the lifeless boy on the ground.

He thought of digging a grave but remembered he had no hoe. All he had was a panga and soil, and branches and tree stems. He could not dig a grave. Abu dragged Phirimoni’s body for ten metres towards a narrow gorge along the west slope of Kyabihambe Hill.

Abu stood, arms shaking, legs cold, left eye twitching, , his hands bruised and tired, his conscience deeply disappointed at how he had mismanaged his rage. A dark cloud stood over Kyabihambe hill and Phirimoni lay in a ravine, his body wrapped in red swollen cuts, blood oozing from the panga inflicted wounds, his breath, still.

He went back to the place he had abandoned the sack of grass and dragged it towards the ravine. Abu poured the green clumps of grass on top of Phirimoni’s body. He dragged the branches he had cut earlier to the ravine and threw these over Phirimoni’s body.

Abu cried warm salty rivers and prayed for the skies to wash him clean of all the blood. His red-pepper eyes looked at the ground where the panga had risen and fallen upon a young boy and he wished for the rain to fall heavily and wash clean the clearing in front of his wood-mountain. He looked at the wood-mountain, saw how it stared back with condemnation, felt the wailing of all the trees he had cut down, all the leaves he had shed, all the blood he had shed.

The sky bellowed and sparks of lightning lit up the dark cloud in streaks of silver. Clear drops of water started to fall from the sky. Abu run and his bare chest rose and fell with each breath he took. The drops increased and red rivers run down his legs as the rain drenched his black shorts.

Two boys waited to be found that December the 11th; one buried in a ravine on Kyabihambe Hill, in red and green wraps, the other running as far away from Kyabihambe Hill wrapped in rain and regret.

Daphine Arinda is a writer and lawyer. Three tenets guide her writing; strip off any inhibitions and write as nakedly as you can, do not sacrifice intricacy for readability, write from a point of knowledge. Arinda writes because it is fulfilling to capture LIFE in words and translate it to art so that posterity may behold authentic Ugandan literature. Her Blog Evabella is a manifestation of the art, thoughts and experiences of a Fearless, Dynamic and Revolutionary writer. She is also a Member of the Advisory Committee of Network of Public Interest Lawyers (NETPIL), a member of the Youth for Policy Think Tank and a social justice blogger at KWEETA Uganda.

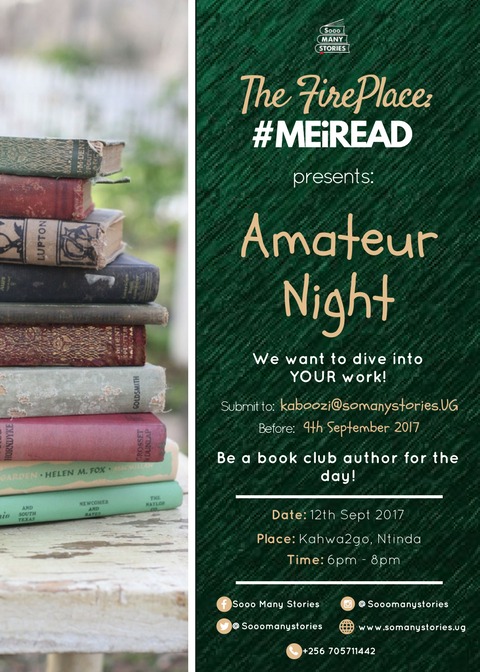

#AmateurNight stories were submitted by writers during our previous #MEiREAD Amateur Nights. During Amateur Night, writers share unpublished work and receive feedback from member of the book club. Tell us what your thoughts are in the comments section.