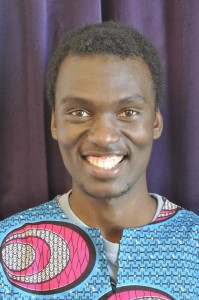

Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire is a writer and law graduate of Makerere and Central European Universities. He is a British Council Global Change-maker, a Harambe Entrepreneur Alliance Associate, a Youth Advisor to Washington, a Generation Change Uganda Chapter member and a Do School Theater Fellow. His work has appeared in literary and academic publications, including the Uganda Modern Literary Digest, Short Story Day Africa, Saraba magazine, New Black Magazine, AFLA Quarterly among others. Presently, he teaches Human Rights at Makerere University and Law at St. Augustine International University.

Brian is a co-founder of Centre for African Cultural Excellence (CACE), the organisation that brings you Writivism.

Bwesigye was such a delight to chat with. Here is what we talked about:

What is Centre for African Cultural Excellence (CACE) and what inspired you to start it?

Cace was started out of depression. Living in Budapest, where more than 90% of the population speak Hungarian, while studying at an American university and reading so much Euro-centric theory opened a part of me that I had always taken for granted. Cliche? I know it is but my African-ness dawned on me so much in 2011/2.

Not so much was familiar about my surroundings. Yet so much in London was familiar to me. So much in Boston was not new. Hungary was alienating largely because of a lack of soft power that Britain and the US have, thus making London and Boston almost feel like home, yet they are not necessarily Africa.

So, the consciousness as to the lack of African soft power was born of this depression. CACE as an idea was started to promote and develop African soft power. Literature, music, theatre, film etc grow a people’s soft power so much that they feel comfortable living anywhere in the world, because they are present. Soft power guarantees one’s presence in the world. So, at the Harambe Bretton Woods Symposium (HBWS), our team of two (Ateenyi Kyomuhendo and myself) was joined by Naseemah Mohamed and we founded the Centre for African Cultural Excellence.

When did Writivism come in?

Writivism as an idea was born months after the HBWS. It was born at the British Council Global Changemakers Euro-Africa Youth Summit in Brussels. I was part of a Human Rights group that thought that literature does not only entertain, but that literature or art generally is also political in nature. It is activism already, even if the idea it stands for may be art for art’s sake. That in itself, art is activism. So, writing and activism are not different at all, hence the combination of writing and activism into Writivism.

After the summit, we secured a $2,500 grant from Global Changemakers and piloted the project in Uganda. The idea is the connection of literature to reality, through connecting readers to writers, running a mentoring program, workshops, a festival, school tours, a short story prize and public readings.

What has been the response by writers to the Writivism call?

The pilot was warmly received in 2012. We had limited the eligible writers to only Ugandan residents belonging to a 15-25 age group. We received about 50 entries.

This year, we felt confident enough to roll out the program to the entire continent. We recruited a Board of Trustees comprising Zukiswa Wanner, Lizzy Attree, E.C Osondu, NoViolet Bulawayo, Chika Unigwe and Ayikwei Nii Parkes and with their advice we have been able to grow the program further.

We had twenty mentors from all over Africa on the program, held five workshops in Nairobi, Kampala, Abuja, Harare and Cape Town, involving over 60 writers in the process. Entries for the Writivism Short Story prize this year hit the 200 mark and we are excited about the interest in the forthcoming Writivism Festival.

I would say that Writivism has been warmly welcomed by the writing community.

How would you describe the Ugandan writing scene at the moment?

It is easier to describe the Nigerian or Kenyan or South African or Zimbabwean writing scene, I think. May be a case of the ability of the outsider to look in better than the insider trying to describe what they are part of. They may not describe themselves properly because the mirror may tell them lies. But seriously, if you allow me to, I think there is much and not much to talk about the Ugandan writing scene at the same time. This year alone, there are a number of regional writing workshops happening in the country. We are building strong institutions: there is FEMRITE, The Lantern Meet of Poets, OpenMic Uganda and many more. There is a lot of activity. Ernest Bazanye once wrote that Uganda is a publishing desert but with a lot of literary activity.

Unfortunately, it is publishing, whether in print or online that actually shows the literary activity to the outside, but also to the inside. Hence it becomes easier to talk about the Nigerian or Kenyan or South African or Zimbabwean writing scene.

But there is hope, as I have said above. Institutions are growing, and the internet is opening doors that did not exist, or were shut to Ugandan writers before.

What challenges have been cited by writers?

I have heard many bemoan the lack of opportunities. I have heard others claim that they have nothing to motivate them to write. Others say it is not economically viable to write. Some also talk about the reading culture. That it does not exist in the country. On my part, I think (although you have asked challenges cited by writers – not me) that the major challenge is a lack of hunger for excellence and success. The writers are not hungry enough. My mentor, Jackee Batanda, would say not mad enough.

Which writers inspired your interest in writing?

I used to love literature (not writing) from my school days. I admired the authors of the works we studied in school. So, I started off writing, which was really trying to be an Achebe, a Naipaul, a Ngugi, an Armah of my day. Then in my Senior Six, my Literature teacher, the Late Bernard Wafula Mukhata brought me to The Sheraton and The National Theatre to attend sessions of the British Council Crossing Border program. There were various writers in Kampala. I had not read much work written by many of the writers at those events, so I did not pick much inspiration from them, except the confidence that indeed writing is possible in our times. I spent my Senior Six vacation chasing the writing dream. Looking for a computer at NetMedia Publishers where Solomon Bareebe worked, and giving him what I considered well-written manuscripts then. I gave up when I joined Law School at Makerere.

In 2010, as I completed my undergraduate studies, Facebook delivered Nick Twinamatsiko’s Chwezi Code. I loved the book because the story was set in a familiar environment. For the first time in my adult life, I read myself, my relatives, my people, my times etc in a novel! But at that time, I was more inspired to market/promote local literature, than to write.

Along the way of doing this, I have since met more writer-preneurs. Writers who are also entrepreneurs whose business is promoting writing. Think Achebe, and what he did with African Writers Series. Think Binyavanga and what he is doing with Kwani?, Rachel Zadok and what she is doing with Short Story Day Africa, Hilda Twongyeirwe and what she is doing with FEMRITE, Goretti Kyomuhendo and what she is doing with African Writers Trust, Jackee Batanda with Success Spark and Beverley Nambozo and her BN Poetry Foundation. These are the writers who inspire me to date.

But as you see, they inspire my interest in being a writer-preneur, with emphasis on the -preneur. I think all writers need entrepreneurship skills. I think we need more writer-preneurs than just writers.

Which Ugandan writers do you enjoyed reading?

Okot P’Bitek. Cliche? Maybe. But I love his Acholi-Nglish. But of course I am also a keen student of his philosophy. I wish all his work was compulsory reading to every Ugandan, especially the collection of his essays Artist, the Ruler. I wish he were alive today. I think he died too young. Reading him is sheer pleasure, but also a good kind of ‘incitement’.

Why should we write?

I do not know. Most of the time I write because I am angry; to rant or heal myself of whatever ills I still harbour. To liberate myself. But I also write because I must. The most eloquent reasons for writing have been given by my favourite Indian writer and activist, Arundhati Roy. She says:

“Writers imagine that they cull stories from the world. I’m beginning to believe that vanity makes them think so. That it’s actually the other way around. Stories cull writers from the world. Stories reveal themselves to us. The public narrative, the private narrative – they colonize us. They commission us. They insist on being told. Fiction and nonfiction are only different techniques of storytelling. For reasons that I don’t fully understand, fiction dances out of me, and nonfiction is wrenched out by the aching, broken world I wake up to every morning.”

This is why I write more non-fiction than fiction, I think. It is “wrenched out by the aching, broken world I wake up to every morning,” and this happens even when living outside Africa.

Why should we read?

I think as long as we are alive, we should read, to remain alive. This is like asking me why we should eat. To stay alive. Because those who do not read are dead? I think. (If we interpret reading widely to include listening to literature. I believe that there is such a thing as oral literature, so bear with my comparison.)

From childhood, even before I learnt how to ‘read’ and ‘write’, I was already reading (by listening to) folktales. Stories are life and there is no life without stories. Without reading. Stories are like food. A basic need, we can’t do away with.

There is a school of thought that chastises writers that write for competitions. They say writing for competitions affects the writers’ creativity as they are forced to write a certain way to ensure they win. Infact, it was William Faulkner that said, “I’ve never known anything good in writing to come from having accepted any free gift of money. The good writer never applies to a foundation. He’s too busy writing something.” What are your thoughts on this? What are the pros and cons of writing for competitions?

I disagree. Context is everything. Some people send their stories to competitions in order to earn credibility. Some target the amount of money on offer. Some want to develop their craft because competitions at times are more than just the money. There are competitions like Writivism, the Caine Prize etc that include workshops, mentoring and other things that develop the writer’s craft beyond the money.

Most probably it is populated majorly by writers who failed to win any competition; a sourgraper’s paradise. To reduce writing competitions to the prize money is a great sin.

What are some of the most common mistakes writers make when they apply to the competition?

Not following the most basic of instructions/guidelines. Word-counts for example. Even inclusion/exclusion of personal details. It is not rare to find a manuscript that has a name, yet the instructions clearly state that no mark as to the identity of the writer should be included. Or some other simple guidelines like send the story as an attachment, and you find the story in the body of the email. And sometimes it is the good writers, those whose stories will no doubt enthral the competition judges that make such basic mistakes.

Sometimes this costs them the entire competition, and other times they survive, depending on who is administering the prize.

Next week, Bwesigye will be back to tell us everything that we need to know about the Writivim Festival.

[…] Read the entire interview here. […]

[…] week, Bwesigire bwa Mwesigire talked to us about CACE, writing competitions and why we should read. This time, he tells us what we must know about the upcoming Writivism […]